Lovis Corinth: Lovis Corinth

Galerie Karsten Greve Paris

Tuesday to Saturday, from 10am to 7pm

Opening

on Saturday, January 29, from 5pm to 8pm

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue.

LOVIS CORINTH - Galerie Karsten Greve Paris - 2022. © Nicolas Brasseur

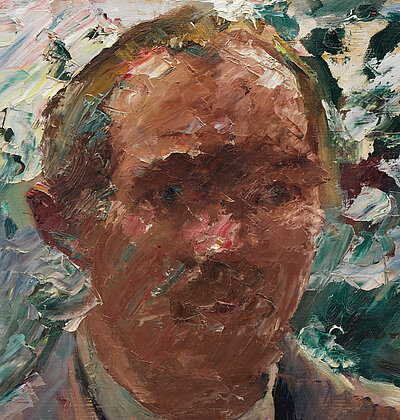

Galerie Karsten Greve has the honour of presenting its first exhibition dedicated to the German painter Lovis Corinth (1858‑1925), exhibited by an art gallery in France for the very first time. The works showcased shine the spotlight on his later period through a series of 11 pieces – a work on paper from 1918, a self‑portrait from 1922 and nine floral still lifes carried out between 1915 and 1925. These works from the Greve Collection invite viewers to rediscover this visionary artist, celebrated throughout his lifetime, but whose legacy was eclipsed by the socio‑political turmoil of the 20th century.

Upon his return to Germany, Lovis Corinth turned from academicism and became one of the founding members of the Munich Secession in 1892, leaving after only one year. In 1901, he settled in Berlin and joined the Berlin Secession. He was elected its president in 1915. There, he met Paul Cassirer, influential art dealer of Jewish descent, who was the first to exhibit his works in his gallery and who introduced him to a new elite that sought more contemporary art. Thanks to Cassirer, Corinth became very familiar with the works of Paul Cézanne and Vincent Van Gogh. He admired both solitary geniuses who had turned from the conventional art centres, restrictive rules and burdensome expectations of society to get back to the intoxicating freedom of gesture and colour. In 1913, the biggest exhibition during Corinth’s life took place, held by Cassirer and totalling almost 230 works. In 1918, on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday, Lovis Corinth was hailed as a genius by the Germanic press, the “Master of German impressionism”. His landscapes and still lifes received a critical reception that was more than enthusiastic. Thirteen of his paintings were selected to represent Germany in the Venice Biennale in 1922, alongside Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt and Oskar Kokoshka. The virtuoso technique, bold framing and vigorous strokes cherished by Corinth were reflected in the works of his contemporaries such as Edvard Munch, then, 30 years later, in the painting of the New York School and abstract expressionists.

Lovis Corinth’s oeuvre does not lend itself to a stylistic definition – now expressionistic, now impressionistic, the artist would meld movements in a kaleidoscope of inspirations. Born in Tapiau, East Prussia, in 1858, Corinth witnessed the Franco‑Prussian War and the unification of Germany. Drawn to art from a very young age, he was given extensive artistic training, which spanned more than 12 years, at the art academies in first Königsberg (1876‑1880), then Munich (1880‑1884) and, finally, Paris, where he studied under William‑Adolphe Bouguereau and Tony Robert‑Fleury at the Académie Julian (1884‑1887). When he arrived in the French capital in 1884, he discovered a Paris disturbed by the incessant change of regimes, the defeat against Prussia and social and economic crises. Recollections of the bloody Paris Commune and its civil violence haunted the memory of a society destabilised by the urban reorganisation undertaken by Baron Haussmann. Despite that, Corinth excelled in Paris. In the second half of the 19th century, a young artist had to submit to the academic system to be successful, the honours of the Salon de Paris signifying the height of success. Corinth exhibited at the Salon in 1890 and received an honourable mention for a Pietà, thus achieving that rite of passage, but he did not stop there.

The paintings carried out between 1923 and 1925 represent the summit of that effervescent expressionism. In the oil on wood Blumen im Bronzekübel, 1923, Lovis Corinth celebrated the gesture that, little by little, transfigured reality to highlight his emotions. It is a free painting that exalts the palpable pleasure of the act of painting and demonstrates great sensuality in the creative process. “Bust portrait, dark against luminous sky. In the background leaves and a piece of the lake visible. Painted in Urfeld am Walchensee on the terrace of our country house” is how his wife Charlotte Berend‑Corinth described the 1922 self‑portrait, one of the only self‑portraits currently in a private collection. Lovis Corinth painted himself at least once a year after 1900, fascinated by the passing of time. In this painting, he played with the suggestion of the shape of the lake, recognisable through fresh colours typical of the region, which make the browns and warm beiges he chose to represent himself stand out. Only colour distinguishes landscape from figure through a daring ballet of brush strokes. On 31 March 1925, Corinth wrote in his diary: “True art means using unreality. This is the highest goal!”. It is thus no longer mimesis that is important, but a raw, sensual plastic equivalent, in harmony with expressionism, which reflects the mood.

"Flowers, the most suitable subject for still lifes, have delicate and subtle shapes and blossoms and petals."

Lovis Corinth

Corinth’s aura lasted until the beginning of the 1930s and the rise of Nazi ideology. In July 1937, some of Lovis Corinth’s works were included in the Munich exhibition Entartete Kunst (“Degenerate art”) next to works by Picasso, Kokoshka, Munch, Chagall, Nolde and many more artists. The reasons were his later paintings and the energetic brush strokes for which he was renowned. These works in particular were described as careless, ill, “degenerate”. Married to a Jewish woman and supported by great Jewish collectors, Corinth became an artist non grata in the eyes of the Third Reich.

In the same year, on 25 April 1937, the American Edward Alden Jewell wrote a laudatory article on Lovis Corinth’s exhibition at the Westermann Gallery in New York in The New York Times: “It was an unforgettable experience. […] At a stroke infinitely subtle and magnificently savage, the most characteristic of his canvases take one’s breath. They stir and evade and challenge and in the end reward with a sense of essences made tangible”, thus preserving the artist’s ingenious brilliance outside Europe.

By unveiling this exhibition in the French capital, Galerie Karsten Greve honours this artist and his legacy, which would be reborn a few decades later in the works of Willem de Kooning and Cy Twombly.

Every one of these eleven exceptional works presented by Galerie Karsten Greve highlights the complexity of his work, between poetry and social drama. Ritterrüstung und Schwert, a work on paper from 1918, attests to the artist’s desolation in the face of political upheavals and the fall of the Empire, represented in the shattered armour of a knight, formerly a glorious figure in the artist’s universe. The nine still lifes, on the other hand, demonstrate the evolution of his plastic research. Chrysanthemen im Krug, 1918, represents a floral frenzy that echoes the chrysanthemums painted by Gustave Caillebotte and the representations of the garden at Giverny that so enthralled Claude Monet. From 1919, idea, invention and formal dissolution were often one and the same and led to a dematerialisation of the subject. For one who looks, the experience of these still lifes is not simply visual. The texture of the painting vibrates with a feeling of electrifying energy and seems to come to life. Corinth managed to hint the special fragrance of lilac, roses and anemones; he painted the aura of things. In the composition Amaryllis, Flieder und Anemonen, 1920, the flowers burst out of the frame to draw the viewer into the space of the painting. By blurring the line between figuration and abstraction, shape becomes secondary – sometimes suggested, sometimes clear – as in Flieder im Kelchglas, 1923, in which subject and background blend in shades of blue. An admirer of the Dutch masters, particularly Rembrandt and Frans Hals, Corinth associated pictorial tradition with his own modernity. He oscillated between realistic representation and the raw emotion that came from his perception of the world. In 1920, he wrote in his teaching manual: “Flowers, the most suitable subject for still lifes, have delicate and subtle shapes and blossoms and petals”. By painting that floral diversity, Corinth tamed a motif that has an infinite variety and never stopped rising to the challenge.