South America

Galerie Karsten Greve Paris

Dienstag - Samstag 10 - 19 Uhr

Vernissage

am Samstag, 28. Mai 2022, von 17 bis 20 Uhr

Galerie Karsten Greve is pleased to present SOUTH AMERICA, a new group show of contemporary works by James HD Brown, Jose Dávila, Lynn Davis, Lucia Laguna, Maria Nepomuceno, Ernesto Neto, Tomás Saraceno and Sergio Vega which are informed by the myths and legends of South America. Gabriel García Márquez said that “surrealism comes from the reality of Latin America” while Alejo Carpentier championed “magic realism” (in literature and in the arts) as inherent to both Americas. Pre-Colombian communities made no distinction between the natural and the supernatural; tales, myths, legends and the imaginary were woven into daily life.

This notion of “magic realism” runs through the exhibition at Galerie Karsten Greve. Viewers are invited into a world that is part dream, part reality. A world whose oxymoronic narratives both surprise and delight.

The paintings of Lucia Laguna (b. 1941 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) show elements from nature alongside more peculiar objects. In Jardim n. 35, a painting from 2016, the impression is that of different worlds coming together. Laguna paints what she sees from her studio and also takes inspiration from the objects and elements around her. Luxuriant jungle foliage in a palette of greens spreads over bands of blue and beige tones – those of Rio de Janeiro’s sky, sea and beaches. Meanwhile, a curious collection of vases spills off the edges of the canvas. The true magic of Laguna’s paintings reveals itself in the viewer’s interpretation of the mysterious details that inhabit these multiple layers.

Sergio Vega (b. 1959 in Buenos Aires, Argentina) has travelled South America in search of an untouched paradise. His photographs of the Amazon rainforest with its lush vegetation, such as Ruben’s Twist 1, from 2011, encourage us to rediscover “nostalgia for the Garden of Eden”; what Mircea Eliade called “Primordial Time”. Vega’s work is also a reflection on post-colonial history and heritage, and its impact on communication and language. For example, Language/Color, a collage from 2009, calls out to Piet Mondrian’s revolutionary pictorial language. Vega, a university professor, questions the continent’s very identity, extending between the traditions and relics of past civilisations and colonialism. The parrot, described by the artist as “stereotypical exoticism”, is the central figure of this reflection. Vega’s Parrot Theory is an interdisciplinary project through which the artist formulates his research into identity and communication. The parrot is a means of investigating language and, moreover, communication, which are the foundations of identity. His Postcolonial Victory – a resin replica of the Winged Victory of Samothrace – sports bright green and yellow wings. A possible metaphor for the contemporary identity of a culture that is striving to reconnect with its origins?

Peru 08, Machu Picchu, a large-format photograph, toned with selenium, by Lynn Davis (b. 1944 in Minneapolis, USA), offers an ethereal vision of the ruined Inca citadel. The silvery swathes of mist echo the mystery that drapes over Machu Picchu itself. Goethe wrote “When we say of a landscape that it has a romantic character, it is the secret feeling of the sublime takingthe form of the past or, which is the same thing, solitude, absence or seclusion,” and there is indeed something of the great nineteenth-century German Romantics in the contemplative nature of Davis’s photography. It confronts us with the majesty and power of nature, and with the mysteries of abandoned sites where nature has reclaimed its rights. Writing about Lynn Davis’s work, Patti Smith says: “Where external space leads into inner space. Where the spray of a fall is as dense as the mane of a horse. Where a man disintegrates into rainbow. The artist brings the oneness of these poles into focus. Where one looks through the solid. Where emptiness is charged, clothed in form.”

Dialoguing with the three photographs by Lynn Davis are two sculptures by Jose Dávila (b. 1974 in Guadalajara, Mexico). Panes of glass inserted into slabs of marble or volcanic rock articulate space, defying the laws of equilibrium. Ironically, because they have been removed from their natural environment, these rocks and minerals are stripped of their innate function; they exist only in their relationship with the viewer, who feels compelled to move around the sculptures and peer through the glass. The border between real and imagined is blurred, becoming dreamlike, supernatural almost – like a mirror leading to a parallel world – while the stones combine into an abstract topography.

Foam 68np/Mn, a 2017 installation by Tomás Saraceno (b. 1973 in San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina), is constructed from metal, nylon, fishing nets and wire. Its web-like form links it to the artist’s wider Arachnophilia project, which stems from years spent observing spiders and their webs. Weaving metal and wire, Saraceno imitates these fragile structures on an infinitely larger scale. These structures are works of architecture and science, and this raises questions about the ignorance and arrogance of our anthropocentric society. Saraceno wants us to question our place in the world: “What can we learn from animals? From Indigenous groups? From the cosmos? What if we could communicate with spiders? Is Earth floating or flying? Why aren’t humans more trusting of their instinct?”

From webs to weaving, a tradition of pre-Colombian civilisations. Maria Nepomuceno (b. 1976 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) borrows from ancient artisanal techniques to create abstract forms out of rope and fibre. The handcrafting of each piece – a fundamental process in Nepomuceno’s art - connects the artist with the work and also draws the viewer and the work together. Untitled (2008), made from braided rope and beads, snakes across the gallery floor like a jungle vine, where it invites the viewer to move around its immediate space. Nepomuceno’s organic language recalls that of another Brazilian artist, Ernesto Neto (b. 1964 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). However, unlike Nepomuceno, Neto uses synthetic materials. His Phytuziann (2006) is an accumulation of polypropylene pellets and Lycra mesh whose biomorphic form begs to be touched.

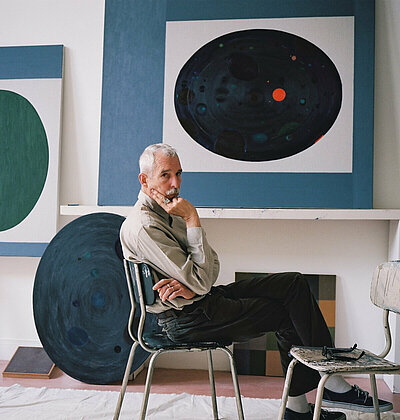

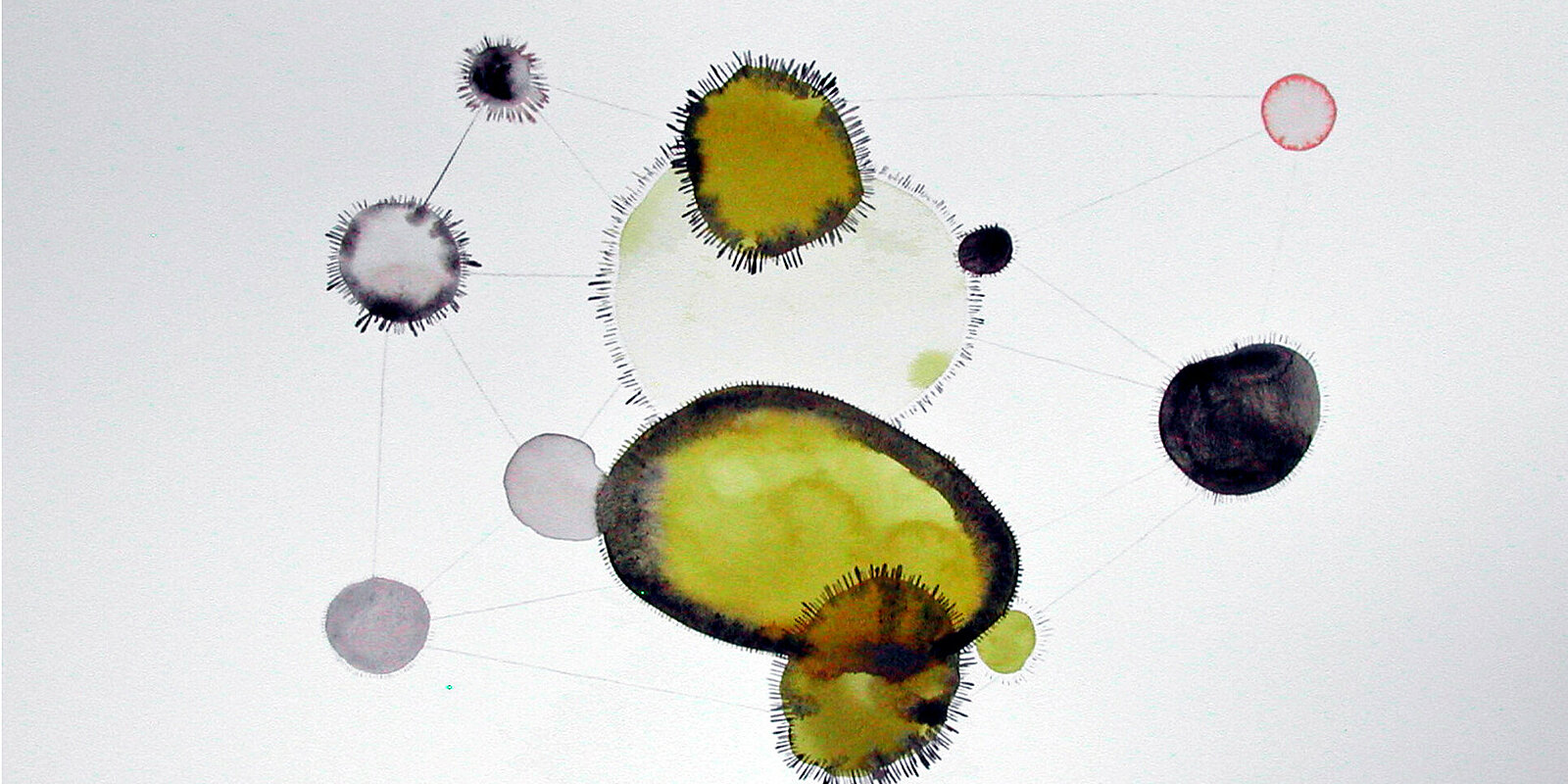

James HD Brown (b. 1951 in Los Angeles, USA, d. 2020) shared his time between Paris and Oaxaca in Mexico, a region which, from 1995, became his “second home”. Six works on paper are shown. They are two previously unseen large formats from his Planets series, three mixed media works (watercolour, pencil and collage on papier) from the Caput Mortem series and a work on paper titled Light beam falling on a house crystal 15 times. Dating from 2006, they were all produced in Mexico and are part of the artist’s research into representations of the universe and the cosmos; two important themes in pre-Colombian culture and mythology. Brown draws from the spiritual heritage of Mesoamerican civilisations to create cosmic symphonies. The maelstrom of abstract and organic forms urges the viewer to contemplate infinity and the origin of the world – in other words, a metaphysical reflection on the universe. In the three works on paper from the Caput mortem series (from the Latin “caput” (head) and “mortem” (dead)), two undulating serpents have found their way into the pictorial space. In Maya culture, the serpent, a symbol of humanity, stands for impermanence and the link between the world of the dead and that of the living. The serpent carries heavenly bodies in paradise and connects the terrestrial with the spiritual.

“In his other house, where visions occur, James Brown strides back and forth,” writes the essayist Michel Bulteau. In this other world – where visions occur – there is freedom for those who seek it. Through this selection of works, SOUTH AMERICA pays tribute to the richness of the lands that are inspiration and home for these artists.

List of artists: James HD Brown, Jose Dávila, Lynn Davis, Lucia Laguna, Maria Nepomuceno, Ernesto Neto, Tomás Saraceno, Sergio Vega